One of the traits of this magazine is a tendency to grandiose theoretical explanations. That’s one of the things I like about it; I’m into grandiose theoretial explanations myself. It isn’t scholarly publication, and few of its authors have academic reputations to defend, so that tendency is not always restrained by the standards that keep theorizing under control in academic journals. Sometimes that means that the magazine runs a provocative, bold idea that might not have survived heavier editing; sometimes it means that it runs something that’s just plain cheesy quality. Again, I’m a pretty cheesy guy, so that’s okay with me.

One of the traits of this magazine is a tendency to grandiose theoretical explanations. That’s one of the things I like about it; I’m into grandiose theoretial explanations myself. It isn’t scholarly publication, and few of its authors have academic reputations to defend, so that tendency is not always restrained by the standards that keep theorizing under control in academic journals. Sometimes that means that the magazine runs a provocative, bold idea that might not have survived heavier editing; sometimes it means that it runs something that’s just plain cheesy quality. Again, I’m a pretty cheesy guy, so that’s okay with me.

For example, this month Ted Galen Carpenter points out that Americans by and large are quick to view political disputes in foreign countries in a romantic light, seeing the ghost of Thomas Jefferson in all sorts of unlikely figures. The next piece, by John Laughland, picks up on this same theme, explaining this American tendency as a sign of the influence of the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Laughland writes that “the key to understanding the West’s love of revolutions” is Westerners’ characteristic desire to believe that “politics can and should be a story with a happy ending.” This desire has run rampant in the West ever since the thinkers of the Enlightenment undermined the traditional Christian belief that the cosmos was ordered in a hierarchy, that justice was to be found in that hierarchy, and that the ruler’s power should be limited because the ruler was subordinate to God. Laughland identifies Immanuel Kant as “the greatest of all Enlightenment philosophers,” and summarizes Kant’s theory as a belief that ordinary reality is unknowable, but that the highest reality is “the categorical imperative- an abstract universally valid proposition that becomes real when it is willed.” Proceeding from these rather drastic simplifications, Laughland declares that:

The attraction of Enlightenment liberalism, therefore, is the result of a deep emotional need for a philosophical sytem that enables man to create a reality in a universe he does not understand and thereby to escape from the difficulties of the world by believing that everything will turn out all right in the end. Lacking a real belief in the afterlife, it also holds that the drama of human salvation is played out in this world, in history and politics.

Again, this is a severe oversimplification, but it has a certain plausibility. Where Laughland really goes off the rails is in his closing section, in which he argues that Enlightenment liberalism has an “objective ally” in Islam:

[B]ecause it has no priesthood, Islam, and especially Shi’ism, is fundamentally a “democratic” religion comparable to Puritanism and other forms of Presbyterianism. There is no established hierarchy; the Koran must be read equally by all. Of course Allah is supreme and Islam demands absolute submission to Him; on the face of it, this seems the opposite of the liberal model in which the individual is subjected only to himself. But this very submission is egalitarian, creating a mass of individuals who are equal in their abstractness. Moreover, God’s will is [merely] will, it has no correlation with natural law as in the Christian or Jewish traditions. Islam is therefore a profoundly voluntarist religion. Because Allah is absolutely transcendent and unknowable, he is like the Kantian thing-in-itself: mere command.

(more…)

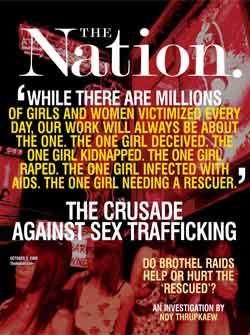

We take sexual violence seriously here at Los Thunderlads, and so welcome the first installment of The Nation‘s investigation of sex trafficking and of what’s being done in the name of stopping it. The first part looks at some projects that don’t seem to be helping; the second part will look at other approaches that might represent an improvement.

We take sexual violence seriously here at Los Thunderlads, and so welcome the first installment of The Nation‘s investigation of sex trafficking and of what’s being done in the name of stopping it. The first part looks at some projects that don’t seem to be helping; the second part will look at other approaches that might represent an improvement.