Most of the links below worked when I tried them this afternoon, and several lead to sites that are still updating.

Comics

(This page most recently updated 20 January 2019)

Comics

- Bad Reporter, what the front page of the newspaper might as well look like

- Basic Instructions, “Your all-inclusive guide to a life well-lived”

- Black Cat and Star Pilot, interesting comics that look like they are from the American southwest

- Blondie, which may be over 80 years old, but is still fascinating to look at

- Bug Martini, “random nonsense five days a week”

- Chainsawsuit, by the prolific Kris Straub

- The City, John Backderf (aka “Derf”) expresses his frustration with the US political scene

- Cul de Sac, a strip following in the tradition of Peanuts, by imagining children as less-inhibited adults

- DailyKos comics section, including Tom Tomorrow, Slowpoke, and others who express frustration with the US political scene

- The Dark Side of the Horse, which is sometimes over Acilius’ head

- Deep Dark Fears, by Fran Krause

- Diesel Sweeties, by Richard Stevens III (alias “R. Stevens”)

- Dinosaur Comics, T. Rex ‘n’ friends have a series of bull sessions

- Doghouse Diaries, no dogs in sight

- Existential Comics, “a philosophy comic about the inevitable anguish of living a brief life in an absurd world. Also jokes.”

- Foxtrot, updates Sundays

- Garfield Minus Garfield, which makes us wonder how they keep “Garfield” from being funny; Arbuckle does the same thing; the Square Root of Minus Garfield tries a little too hard

- “Too Much Coffee Man,” a.k.a. How to Be Happy, by Shannon Wheeler

- Imagine This, quietly brilliant gag-a-day strip

- Indexed, Jessica Hagy uses charts and graphs to analyze some really important relationships

- Junior Scientist Power Hour, by Abby Howard

- The K Chronicles, cartoonist Keith Knight (who also does The Knight Life)

- Lunar Baboon, a guy who wants you to know he’s a cool dad

- Medium Large, cats, comics, and other things that ought to be sharp

- Monty doesn’t really stand out as a black-and-white strip in a daily newspaper, but look at it in color and you’ll be a fan

- Mutts, Patrick McDonnell reimagines Krazy Kat and Ignatz in a gentler light, with Ignatz transformed from mouse to dog

- Mythtickle, in which Justin Thompson goes places Asterix never quite got round to

- Nancy, which has gone to surprising places

- The Oatmeal, achingly beautiful stories about dogs mixed in with other stuff

- Oglaf, weekly strip that is to sex what xkcd is to math

- Please Listen to Me, about how things change when you change your perspective

- Raghead the Fiendly Neighbourhood Terrorist, a creation of Biswapriya Purkayastha, who denies that he is “a nice person in any sense of the word”

- Retail, which shows that a serial strip can be drawn in the style of a gag-a-day strip and still work

- Robbie and Bobby, “about the indestructible friendship of a robot and his boy”

- Sarah’s Scribbles, Sarah C. Andersen lays it on the line Wednesdays and Saturdays

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, the world of some grumpy grad student

- Scenes from a Multiverse, remarkably mild

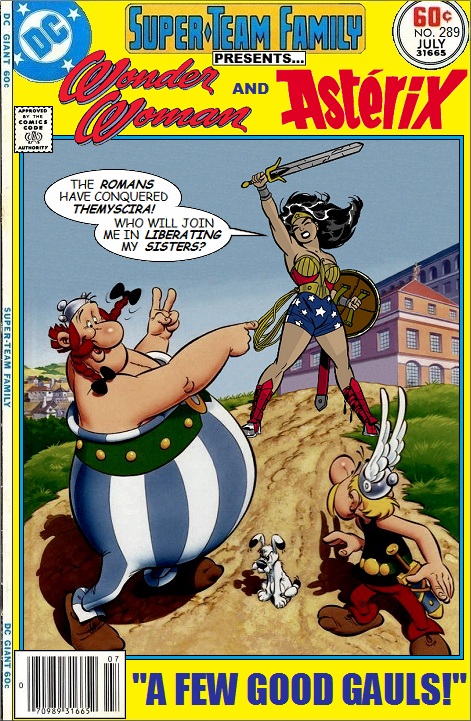

- Super-Team Family, covers of imaginary comic books, in which established characters are teamed in unlikely ways

- Ted Rall is a US political cartoonist who opposes both the Republicans and Democrats, just because of their shared habit of murdering defenseless people. Picky, picky.

- Three Word Phrase, Ryan Pequin’s gag-a-day webcomic

- Tom the Dancing Bug, Ruben Bolling expresses his frustration with the US political scene (he also does Super-Fun-Pak Comix, which is great)

- Two Party Opera, where dead and not yet dead US presidents hang out

- Unshelved, a strip by librarians, about librarians, for librarians. If you’re a non-librarian and you read it, you’re a voyeur.

- Wondermark, looks like 1896, reads like 1996

- xkcd, stick figures who enjoy math; and what-if, in which similar figures stand by watching helplessly as physics is used to answer hypothetical questions

- Zen Pencils, by Gavin Aung Than, who calls it “a website where inspirational quotes from famous people are adapted into cartoons”

Less Frequently Updated

- Sarah E. Laing’s “Let Me Be Frank“; she used to do “Forty Four Ways of Looking at an Apple” also

- Lead Paint Comics, by Mike Cornnell and Dana Wulfekotte (it seems that Mike Cornnell’s name actually does have two “n”s in it)

- Lucy Knisley moves around a lot, this link worked last time we updated this page (here’s her tumblr)

- Marlo Meekins, not for the squeamish

- Occupy Comics Shazam, doesn’t include Shazam or the Mighty Isis, but is worth reading anyway

- Outnumbered, by Tom Bancroft

- Poorly Drawn Lines, by Reza Farazmand

- Spiked Math, complex reasoning, simple hilarity

- Unwinder’s Tall Comics, a web comic about people who try to entertain themselves without using the web

- With Fetus, by D. Murphy and Emily Ansara Baines, who say “It’s About Abortion!” An interesting strip, but the art is terrible.

News and Comment

An alphabetical list

- Cartoon Research, compiled and edited by Jerry Beck

- Christ, Coffee, and Comics, Greek Orthodox priest Niko Bekris explores the theological depths hidden in stories about Superman

- Comic Book News Service, “a comic book community where fans find reviews, news, special features, and a column for every day of the week”

- Comics Curmudgeon, Josh Fruhlinger reads the funny papers

- Comics Reporter, “Tom Spurgeon’s Web site of comics news, reviews, interviews and commentary”

- Escher Girls, what the comics think a woman is

- Fleen, “home of the webcomics Action News Team”

- God and Comics, a podcast in which three Episcopal priests demonstrate that, no matter how erudite and accomplished you are, if you’re a grown man talking about why he likes Batman, you’ll start to sound like a stoner

- A Good Cartoon, was funny at first, but seems to be heading down a bit of an angry political rabbit hole right now

- I Love Ya But You’re Strange and other things by Brian Cronin (the revealer of legends)

- Language Log’s “Linguistics in the Comics” section

- Shitty New Yorker Cartoon Captions, in which the shittiness of the captions illustrates the shittiness of the cartoons

- Stripper’s Guide, revisits newspaper strips and comic panels of days gone by

- Team Cul-de-Sac

Archives and Graphic Novels

An alphabetical list

- The Bad Chemicals, “a sad and silly comic” by some guy named Brent

- Carbon Dating, “a comic strip about science, pseudoscience, and geeky relationships”

- Captain Confederacy, which imagines what the world might be like if the Confederacy had won the US Civil War, and superheroes were real, and the ruling elite of the Confederacy manipulated those superheroes into perpetuating white supremacy. You know, the obvious questions everyone asks when they study the history of the 1860s. It’s kind of like its contemporary The Watchmen, only with a focus on mass media as a regressive force in race relations.

- The Comic Torah, Aaron Freeman and Sharon Rosenzweig reimagine “the (very!) Good Book”

- Comics With Problems, comics that address themselves to social problems, but which themselves represent other social problems

- DAR: A Super Girly Top Secret Comic Diary, by Erika Moen

- Dead Philosophers in Heaven, which would make Lucian proud

- Dykes to Watch Out For archive, selections from Alison Bechdel’s great strip

- “Hark! A Vagrant!” Canadian Kate Beaton’s “comic about failure”

- Ignore Hitler, a title that would have been good advice to voters in the Weimar Republic, a comic that appeals to some people, for some reason

- Tony Millionaire’s Maakies, which picks up where the Katzenjammer Kids may someday leave off

- Planet of Hats, a Star Trek Recap Comic

- Request Comics, which somebody must have asked for

- Thinkin’ Lincoln, heads of famous historical figures are associated with improbable remarks

- Troubletown, Lloyd Dangle expressed his frustration with the US political scene

- “White Boy,” later known as “The Adventures of White Boy in Skull Valley,” later still as “Skull Valley,” was a newspaper strip that artist Garrett Price drew for a few years in the 1930s. This site has scans of a couple of strips, along with a biographical note about Price; this site has a larger selection of strips; a 2005 special issue of Comics Journal featuring the first 32 “White Boy” strips is available to Comics Journal subscribers here.

- Working at the Death Star, what all those guys in the background probably did on days when R2D2 and his friends weren’t around