Quite possibly the best scene from any movie in the teens-in-a-cabin-get-mutilated genre:

All posts in category Art

Cabin Fever: Pancakes!

Posted by CMStewart on December 13, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/12/13/cabin-fever-pancakes/

They shall beat their swords into plush chairs

Thanks to haha.nu for posting about The Peace Art Project Cambodia, which turned decommissioned small arms into furniture and sculptures.

Posted by acilius on December 10, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/12/10/they-shall-beat-their-swords-into-plush-chairs/

The Nation, 22 December 2008

It’s usually the reviews that feature most prominently in my notes about The Nation. That’s because the notes are about things I might want to look up again, and The Nation‘s articles and columns are usually of strictly timely interest. This week’s issue is no exception.

In this issue, Arthur Danto reviews a retrospective of Giorgio Morandi‘s paintings currently showing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’ve always had a fondness for Morandi’s subdued color schemes and restricted perspective. Danto claims that the objects in Morandi’s still lifes seem much more active than is typical for the genre; sometimes they seem “to interact and jostle” as if competing for space on the table. He cites this 1961 painting as an especially crowded one. He may be onto something; for example, this 1914 piece does seem to point forward to the Futurists. But more often when I look at Morandi I see pictures like the one I’ve posted here, quiet images that neither call out for attention with flash nor resist the viewer with trickery, but, rather, allow those who are so minded to take whatever look they wish.

Throughout a review of a reissue of Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination runs the question of what it might mean for literature to have, as Trilling always insisted it should have, a serious moral purpose. Trilling tries to answer the question with a remark about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, an answer the reviewer finds unsatisfactory:

“No one who reads thoughtfully the dialectic of Huck’s great moral crisis will ever again be wholly able to accept without some question and some irony the assumptions of the respectable morality by which he lives, nor will ever again be certain that what he considers the clear dictates of moral reason are not merely the engrained customary beliefs of his time and place.” One response to this might be to say that anyone capable of this kind of “thoughtful” reading is not likely to be a prisoner of social convention in the first place, and vice versa. The passage risks both patronizing the imagined reader and imputing an unrealistic power to Twain’s book. In such passages, the adjective “moral” appears overworked, now indicating the merely conventional social codes, now referring to the wider human vision offered by the critic.

A fair criticism, one must admit. Humanists from Plato on would have to plead guilty to the charges the reviewer levels against Trilling here.

Elsewhere in the issue, Katha Pollitt quotes New York University historian Linda Gordon, a founder of Feminists for Obama, calling on feminists to keep up pressure on Mr O, since that’s what their opponents will be doing. She also quotes an op-ed by economist Randy Albelda calling for increased investment in health, education, eldercare, and other industries that employ many women as part of any economic stimulus plan. Alexander Cockburn points out that in the aftermath of the Mumbai shootings, several top Indian officials were driven from office in disgrace, a stark contrast with the failure of any senior American to so much as admit error in the aftermath of 9/11. Stuart Klawans reviews recent films Milk, Australia, and Wendy and Lucy.

Posted by acilius on December 10, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/12/10/the-nation-22-december-2008/

Chronicles, December 2008

(image)

Three articles about Christmas in this issue of Chronicles. Editor Thomas Fleming, who I seem to recall occasionally describes himself as having been raised an atheist, then converted to arch-traditional Roman Catholicism, describes in the third person the attitudes of an unnamed man who was raised anatheist, then converted to arch-traditional Roman Catholicism. As a boy, this anonymous person disliked Christmas. The months-long buildup, the morning moments unwrapping toys that could never live up to the expectations that buildup engendered, the endless anticlimax of the day as of adult relatives hung on and bored him with their chatter. Far better Halloween, an ordinary day that ended with a burst of total anarchy. As he grew, he preferred the moral atmosphere of Halloween to that of Christmas. The Christians he knew pretended that death was nothing to be afraid of and embedded that pretense into the holiday, while Halloween began by taking the cold terror of death and everything touching death for granted. Evidently this preference remains with him in his religious phase, as the terror of death gives Easter its power.

Contributor Thomas Piatak defends Christmas, not against the severe theology of Fleming, but against opponents of public piety at Christmastime. Apparently it was Piatak who coined the phrase “The War Against Christmas.” While Fleming inveighs against a religious Christmas that soft-pedals or denies the hard truths of lifeand thus denatures Christianity, Piatak fears a secular Xmas that is “devoid of religious or cultural significance or indeed of beauty, with nothing left but multiculturalist pap and tawdry sentimentalism.” As examples of this creeping insipidity, Piatak cites a case in Columbus, Ohio in 2003, when the school district banned a performance of Handel’s Messiah unless equal time were given to “Frosty the Snowman” and “Jingle Bells.”

Columnist Aaron D. Wolf has little use for the idea of a secular “War Against Christmas,” though he does agree that such a thing exists. He tells us of wishing a store clerk “Merry Christmas.” “She looks directly at me, smiling, eyes narrowed, and nods. “Yes. Merry CHRISTMAS!”… It wasn’t a bright, elven (sic) “Yes! Merry Christmas!” She spoke with a knowing, in your face, liberal America air of defiance.” Later: “That Merry Christmas seemed more like a countercultural protest statement, that kind that says, yeah, you’re one of us, or yeah, I’m one of you. One of you… what? Believers in Christ Jesus? … Or perhaps it was one of you proud white Americans.” Wolf’s suspicion that many of those most exercised about the “War Against Christmas” are in fact not very much devoted to Christ at all, but are only interested in sticking it to educated secularists, gains verisimilitude from the high December sales of mugs bearing the slogan “Don’t be a Pinhead.”

Posted by acilius on December 1, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/12/01/chronicles-december-2008/

Crooked Brains

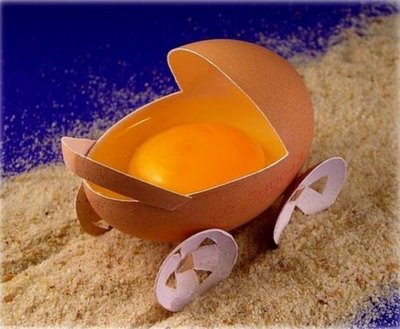

Sometimes I look at Crooked Brains, a website that seems to consist mainly of pictures somebody collected by doing Google Images searches. I first found it while doing a Google Images search to collect pictures for this site. So here are a few of that person’s finds. The captions are mine.

From a post called “Art with Eatables“:

From a post called “Perfect Timed Photos”

Posted by acilius on November 25, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/11/25/crooked-brains/

With that figure!

From yahoo:

Posted by acilius on November 24, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/11/24/with-that-figure/

The Nation, 1 December 2008

Nick Turse looks into American forces’ conduct of the war in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta in the period from 1 December 1968 to 1 April 1969. Turse concludes that the facts were much worse than has generally been known in the USA. Civilians were targeted more systematically than has been acknowledged, more of them were killed than has been acknowledged, and a coverup of the some of the worst atrocities continued for decades. Turse quotes a contemporary letter signed “Concerned Sergeant.” The otherwise anonymous soldier denounced the operations to which he was attached and estimated that the rate at which unarmed civilians were being killed amounted to “a My Lai a month.”

Ever since Studs Terkel died, The Nation has been memorializing him. In this issue, his editor, Andre Schiffrin, remembers their attempt to put together an oral history on the topic of power. The project failed because none of their prospective subjects would even admit that he held power, let alone give insight into what it was like to use it. That’s hardly surprising when Schiffrin describes the key to Terkel’s work. His subjects talked to him, Schiffrin explains, because “he approached people with utter respect. Those he talked to immediately felt this and poured their hearts out.” Powerful people usually seem to expect to be approached with utter respect, if not indeed with abject servility. That so many people from so many backgrounds found it a shock to be approached with respect is a sad commentary on our society.

Hoosiers and others marveling at the fact that Indiana voted for Obama will enjoy Mark Hertsgaard’s piece about Luke Lefever, a plumber (a real one!) who volunteered for the Obama campaign in Elkhart.

Siddhartha Deb reviews several novels by Elias Khoury. At first, Deb praises the “fragmented” style of Khoury’s work as suitable to his native Lebanon, but at the end he suggests that the time may have come for a smoother style of writing and, apparently, a more settled view of Lebanese identity.

This brings us to Barry Schwabsky’s review of Art Worlds by Howard S. Becker and Seven Days in the Art World by Sarah Thornton. Becker’s newly reprinted 1982 book is a sociological study of various milieux from which products came that could be called “art,” while Thornton, also a sociologist, spent her time in “an art world that claims the right to call itself the art world.” Schwabsky puts the question:

In the sociologist’s art world, hierarchies, rankings, and orders of distinction proliferate. Status and reputation are all, and questions about them abound. Why does the seemingly kitschy work of Jeff Koons hang in great museums around the world while the equally cheesy paintings of Thomas Kinkade would never be considered?… How do conflicting views on the value of different kinds of artworks jell into a rough and shifting consensus about the boundaries of what will be considered art in the first place?

That’s quite a weighty question. As for the Koons/ Kinkade riddle, my suspicion is that perspective drawing and the rest of the conventional skills of representational art are not really all that difficult to master. Some years ago I read an essay by Eric Gill called “Art in Education: Abolish Art and Teach Drawing,” in which he argued that given a chance virtually any child could and would learn these techniques. I haven’t seen any scientific work testing this hypothesis, but it doesn’t seem fantastic to me to think that if all children were introduced to art in the same way that, let’s say, Thomas Kinkade was, that some large percentage of the population would grow up to paint pictures very much like his. If that is so, then the problem with Kinkade isn’t that he’s cheesy, but just that they are nothing special. If a collector wants to attain a high rank, s/he can hardly buy paintings that may be very pleasant but that could be equalled by, let’s say, a third of the adult population.

Posted by acilius on November 24, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/11/24/the-nation-1-december-2008/

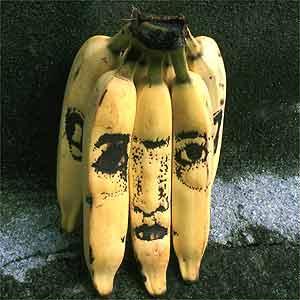

Banana Scrimshaw

Here’s a form of banana art we’ve not yet covered on Los Thunderlads, art made by incising marks into the peels of bananas. For example, this piece by Brazilian sculptor Tonico Lemo Auad, a face made of pinpricks that becomes visible only as the banana rots:

This one, via The Yummy Banana, apparently first appeared on The Tattooed Banana, but it seems to have been removed from that site.

Posted by acilius on November 24, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/11/24/banana-scrimshaw/

Sydney Parkinson’s botanical drawings

Thanks to “The Artist and His Model” for posting a gallery of botanical drawings by Sydney Parkinson. Evidently they found the drawings here. All of the pictures are lovely; I’ve copied a few of my favorites below.

Posted by acilius on November 21, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/11/21/sydney-parkinsons-botanical-drawings/

Human/ Banana Ripeness Chart

From thesneeze, a chart about aging. This chart was posted on 3 October 2004. Michael Fernandes did something very similar at a Nova Scotia gallery four years later, as I noted previously. The posting on thesneeze includes lots of explanatory comments under the pictures, some of them funny, while Fernandes did not include explanatory text with his installation. Also, Fernandes reversed the usual chronology of maturation and decay by setting out fresher bananas each day.

Posted by acilius on November 19, 2008

https://losthunderlads.com/2008/11/19/human-banana-ripeness-chart/