I’m reminded of a little incident that took place five or ten years ago. I teach ancient Greek and Latin in a university in the midwestern USA. I was telling one of my classes, an ancient civilization class conducted in English, about family life in ancient Greece. My explanations usually tend to lean on the brutally economic side, so when I came to the custom of exchanging dowries, everything I said was about the role that dowry exchange played in underwriting joint business ventures between neighboring farmers.

One student who came up to me after this presentation was obviously struggling to restrain her anger. In fact, she was furious with me. She was from India, and when she got married, her family gave her husband a dowry. As she labored to keep herself calm, she explained to me that giving him a dowry wasn’t “about” the economic relationship between the households. It was “about” mutual respect between the families, it was “about” the idea of a common future, it was “about” a pledge to be available to each other in times of need.

Now, I had addressed all of those points in my presentation. But I had subordinated all of them all to the cold facts of the struggle for existence and the high stakes of trust in a subsistence economy. So at first, I just encouraged her to keep talking. After she seemed to have run out of things to say, I asked if she had reason to believe that anything I had said about the ancient Greeks was false. She thought for a second and said no, that it might all have looked that way in the cold light of economic analysis, but that the people inside the culture could never have looked at it in such a light. So I was missing the most important point of the whole custom by presenting it as I did.

The reference to Sherlock Holmes reminds me of an event in a story featuring one of the most appallingly wicked fictional characters ever to anchor a series of popular novels, Brigadier General Sir Harry Flashman, VC, KCB, KCIE. In one of George MacDonald Fraser’s last Flashman stories, 1999’s Flashman and the Tiger, the old reprobate has managed to tangle himself up in some bad business with Sherlock Holmes’ nemesis Tiger Jack Moran. After Moran fails in the attempt, described in “The Adventure of the Empty House,” to assassinate Holmes, Flashman tries to escape arrest and disgrace by flopping down on the street and pretending to be a derelict in an alcoholic stupor. Two characters whom he does not name as Holmes and Watson come near:

If they’ve any sense they’ll just pass by, thinks I– well, don’t you, when you see some ragged bummaree sleeping it off in the gutter? But no, curse their nosiness, they didn’t. The footsteps stopped beside me, and I chanced a quick look at ’em through half-closed lids– a tall, slim cove in a long coat, bare-headed and balding, and a big, hulking chap with a bulldog moustache and a hard hat. They looked like a poet and a bailiff.

“What’s this?” said the bailiff, stooping over me.

“A tramp,” says the poet. “One of the flotsam, escaping his misery in a few hours of drunken slumber.”

“Think he’s all right?” says the bailiff, rot him, and blow me if he wasn’t fumbling for my pulse. “Going at full gallop,” says he, and blast his infernal impudence, he put a hand on my brow. “My goodness, but he’s feverish. D’you think we should get help for him?”

“You’ll get no thanks beyond a flood of curses if you do,” says the poet carelessly. “Really, doctor, even without close examination my nose can tell me more than your fingers. The fellow is hopelessly under the influence of drink– and rather inferior drink, at that, I fancy,” says he, stooping and sniffing at the fumes that were rising from my sodden breast. “Yes, American bourbon, unless I am mistaken. The odour is quite distinctive– you may have remarked that to the trained senses, each spirit has its own peculiar characteristics; I believe I have in the past drawn your attention to the marked difference between the rich, sugary aroma of rum, and the more delicate sweet smell of gin,” says this amazing lunatic. “But what now?”

The bailiff, having taken his liberties with my wrist and my brow, was pausing in the act of trying to lift one of my eyelids, and his next words filled me with panic.

“Good Lord!” he exclaimed. “I believe I know this chap. But no, it can’t be surely– only he’s uncommonly like that old general… oh, what’s-his-name? You know, made such a hash of the Khartoum business, with Gordon… yes, and years ago he won a great name in Russia, and the Mutiny– VC and knighthood– it’s on the tip of my tongue–”

“My dear fellow,” says the high-pitched poet, “I can’t imagine who your general might be– it can hardly be Lord Roberts, I fancy– but it seems more likely that he would choose to sleep in his home or his club, rather than in an alley. Besides,” he went on wearily, stooping a little closer– and damned unnerving it was, to feel those two faces peering at me through the gloom, while I tried to sham insensible– “besides, this is a nautical, not a military man; he is not English, but either American or German– probably the latter, since he certainly studied at a second rate German university, but undoubtedly he has been in America quite lately. He is known to the police, is currently working as a ship’s steward, or in some equally menial capacity at sea, — for I observe that he has declined even from his modest beginnings– and will, unless I am greatly mistaken, be in Hamburg by the beginning of next week– provided he wakes up in time. More than that–” says the know-all ignoramus, “I cannot tell you from a superficial examination. Except of course for the obvious fact that he found his way here via Piccadilly Circus.”

“Well,” says the other doubtfully, “”I’m sure you’re right, but he looks extremely like old what’s-his-name. But how on earth can you tell so much about him from so brief a scrutiny?”

“You have not forgotten my methods since we last met, surely?” says the conceited ass, who I began to suspect was some kind of maniac. “Very well, apply them. Observe,” he went on impatiently, “that the man wears a pea-jacket, with brass buttons, which is seldom seen except on sea-faring men. Add that to the patent fact that he is a German, or German-American–”

“I don’t see,” began the bailiff, only to be swept aside.

“The dueling scars, doctor! Observe them, quite plain, close to the ears on either side.” He’d sharp eyes, all right, to spot those; a gift to me from Otto Bismarck, years ago. “They are the unfailing trade-mark of the German student, and since they have been inexpertly inflicted– you will note that they are too high– it is not too much to assume that he received them not at Heidelberg or Gottingen, but at some less distinguished academy. This suggests a middle-class beginning from which, obviously, he has descended to at least the fringes of crime.”

“How can you tell that?”

“The fine silver flask in his hand was not honestly acquired by such a seedy drunkard as this, surely. It is safe to deduce that its acquisition was only one of many petty pilferings, some of which must inevitably have attracted the attention of the police.”

“Of course! Well, I should have noticed that. But how can you say that he is a ship’s steward, or that he has been in America, or that he is going to Hamburg–”

“His appearance, although dissipated, is not entirely unredeemed. Some care has been taken with the moustache and whiskers, no doubt to compensate for the ravages which drink and evil living have stamped on his countenance.” I could have struck the arrogant, prying bastard, but I grimly kept on playing possum. “Again, the hands are well-kept, and the nails, so he is not a simple focsle hand. What, then, but a steward? The boots, although cracked, are of exceptionally good manufacture– doubtless a gratuity from some first-class passenger. As to his American sojourn, we have established that he drinks bourbon whisky, a taste for which is seldom developed outside the United States. Furthermore, since I noticed from the shipping lists this morning that the liner Brunnhilde has arrived in London from New York, and will leave on Saturday for Hamburg, I think we may reasonably conclude, bearing in mind the other points we have established, that here we have one of her crew, mis-spending his shore leave.”

“Amazing!” cries the bailiff. “And of course, quite simple when you explain it. My dear fellow, your uncanny powers have not deserted you in your absence!”

“I trust they are still equal, at least, to drawing such obvious inferences as these. And now, doctor, I think we have spent long enough over this poor, besotted hulk, who, I fear, would have provided more interesting material for a meeting of the Inebriation Society than for us. I think you will admit that this pathetic shell has little in common with your distinguished Indian general.”

“Unhesitatingly!” cries the other oaf, standing up, and as they sauntered off, leaving me quaking with relief and indignation– drunken ship’s dogsbody from a second-rate German university, indeed!– I heard him ask:

“But how did you know he got here by way of Piccadilly?”

“He reeked of bourbon whisky, which is not easy to obtain outside the American Bar, and his condition suggested he had filled his flask at least once since coming ashore…”

I waited until the coast was clear, and then creaked to my feet and hurried homeward, stiff and sore and stinking of brandy (bourbon, my eye! — as though I’d pollute my liver with that rotgut) and if my “besotted shell” was in poor shape, my heart was rejoicing.

(Pages 309-312 in George MacDonald Fraser, Flashman and the Tiger, London, 1999)

The other day, Aeon published

The other day, Aeon published  )

)

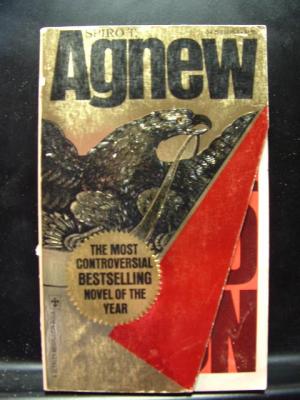

Another book I’ve occasionally seen on shelves but have never read is The Canfield Decision, a novel by Spiro T. Agnew. Mr Agnew will long be remembered as the second Vice President of the United States to resign his office, and the first to do so in disgrace.* Due to its authors notoriety, The Canfield Decision sold well. Few who wrote about it were favorably impressed. Most reviewers focused on the novel’s dreary prose style and poor construction, while the many tactless remarks it contains about the relationship between Israel and American Jews and about the role of American Jews in shaping US public opinion gained a substantial amount of public attention, eliciting reactions ranging from disgust to outrage. I remember

Another book I’ve occasionally seen on shelves but have never read is The Canfield Decision, a novel by Spiro T. Agnew. Mr Agnew will long be remembered as the second Vice President of the United States to resign his office, and the first to do so in disgrace.* Due to its authors notoriety, The Canfield Decision sold well. Few who wrote about it were favorably impressed. Most reviewers focused on the novel’s dreary prose style and poor construction, while the many tactless remarks it contains about the relationship between Israel and American Jews and about the role of American Jews in shaping US public opinion gained a substantial amount of public attention, eliciting reactions ranging from disgust to outrage. I remember