I first became aware of the political question of same-sex marriage in 1980. I was in fifth grade and we were supposed to conduct debates in class about issues of the day. I was assigned to the group opposing this proposition: “The Equal Rights Amendment should be passed.” Researching for my part in the debate, I found an argument that the plain wording of the proposed amendment (“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex”) would grant men the right to marry other men and women the right to marry other women. This was in the context of an article opposing the amendment.

I first became aware of the political question of same-sex marriage in 1980. I was in fifth grade and we were supposed to conduct debates in class about issues of the day. I was assigned to the group opposing this proposition: “The Equal Rights Amendment should be passed.” Researching for my part in the debate, I found an argument that the plain wording of the proposed amendment (“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex”) would grant men the right to marry other men and women the right to marry other women. This was in the context of an article opposing the amendment.

At first I was excited to find this claim. Up to that point all that I had been able to find were dry legal arguments that would never capture the attention of my classmates. Here at last was a point that would grab the imaginations of everyone in the room and hold them for as long as I needed.

But as I thought it over, I realized that there was an obvious question that would stump me if anyone asked it. Why shouldn’t same sex couples be free to marry? The only argument in the article was that same sex couples couldn’t reproduce. My immediate response to that was to think of my grandmother. When my grandfather died, she was in her fifties, most assuredly past childbearing. Yet she remarried, and no one thought to object. So why was the sterility of same sex couples a reason why they should not be allowed to marry?

In the decades since, I’ve kept an eye on the debate. I’ve found some very sensible arguments supporting the right of same sex couples to marry, and some intriguing arguments to the effect that no one should marry. But what I have not found are many substantive arguments in favor of reserving marriage for heterosexual couples. This is quite surprising. One would assume that by now someone would have come up with a worthwhile argument in favor of the status quo.

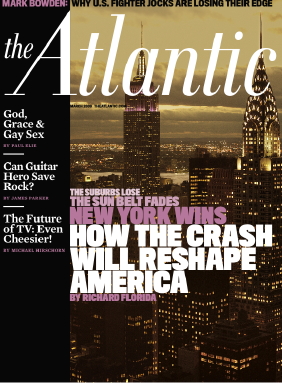

In this issue of Chronicles, Thomas Fleming explains why he is opposed to same sex marriage. (more…)

A profile of Rowan Williams

A profile of Rowan Williams