Chronicles is often criticized for its “neo-Confederate” bent. The two hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth draws that side of the magazine out in force.

Chronicles is often criticized for its “neo-Confederate” bent. The two hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth draws that side of the magazine out in force.

Joseph E. Fallon quotes extensively from Lincoln’s friends and associates to the effect that the sixteenth president had little use for Christianity. He then analyzes Lincoln’s use of religious imagery in his speeches, arguing that he exploited beliefs which he did not share to browbeat his countrymen into supporting a policy of extreme violence and unaccountable executive power. Fallon dwells on the Second Inaugural Address, claiming that the famous passage saying that we must acquiesce in God’s will to punish us for that sin even if “all the wealth piled by the bondman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn by the sword” represents a particularly gruesome moral inversion. “Lincoln assiduously promoted the idea that, while he was blameless for the war, its death and destruction served some higher good.” Fallon closes with a paraphrase of a well-known line which he attributes to Voltaire, that those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.

Thomas Fleming asserts that the Civil War cost the lives of “600,000 American soldiers and perhaps twice as many noncombatants (most of them black.)” I’ve often heard the figure 621,000 as the number of combat fatalities in the Civil War, the other two claims in that sentence were news to me. I don’t know all that much about the Civil War, so for all I know Fleming could be right. He goes on: “Some years ago, when I was debating Lincoln’s legacy, a graduate student asked if I did not think the war that freed the slaves was worth the cost. He was actually shocked that I did not think that hundreds of thousands of dead slaves would have agreed with him.”

The cost of the Civil War to southern blacks is also a major theme of Clyde Wilson’s “The Trasury of Counterfeit Virtue.” “The notion that soldiers in blue and emancipated slaves rushed into each other’s arms with shouts of Glory Hallelujah is pure fantasy,” writes Professor Wilson. Instead, the historical record shows one case after another when Union forces tortured, raped, and slaughtered blacks with impunity. Wilson cites Ambrose Bierce to the effect that the only blacks he saw with the Union army were those whom officers were using as slaves.

Joseph Sobran mentions Lincoln’s statement, from the First Inaugural, that “the Union is much older than the Constitution,” only to dismiss it as evidence that “Lincoln’s knowledge of history was shaky.” I think there’s a bit more to be said for this claim than Sobran allows. Certainly the thirteen colonies that broke away in 1775-1783 had by that time for many years been much more closely linked to each other than any of them had been to other parts of the British Empire.

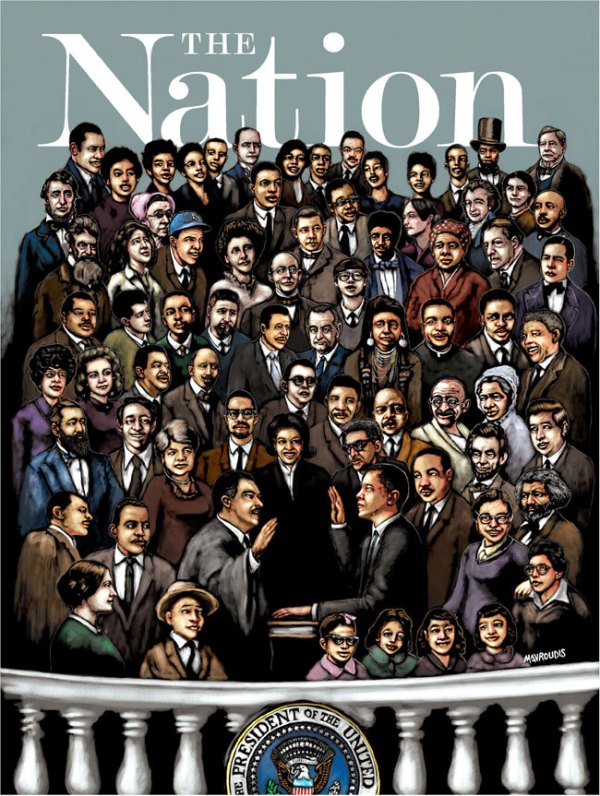

Justin Raimondo, editor of antiwar.com, looks at the comparisons between President Obama and his predecessor that one hears so often these days and takes them with undiluted seriousness. Lincoln, Raimondo reminds us, “suspended habeas corpus, jailed his opponents, and closed down newspapers that displeased him.” Raimondo evidently fears that Mr O’s praise of Lincoln might mean that he plans to follow this example. Lest this fear seem overdone, Raimondo does refer to the powers that presidents between Lincoln and Mr O have claimed for themselves. One rather silly moment in Raimondo’s article comes near the beginning, when he quotes a description of the similarities between these two Illinoisan presidents that mentions the fact that they are both quite thin. “Two thin men? What normal person would make such a comparison? To our elites, thinness is a sign of moral virtue.” Well, perhaps the mention of it is also a sign that Lincoln and Mr O don’t really have that much in common, so that likeners have to draw on the most superficial resemblances.

Daniel Larison, of the Eunomia blog, goes into depth on a theme that Professor Wilson also addressed, the role of Lincoln in fusing Big Government with Big Business and laying the foundations of the corporatist-militarist economic and political system the United States has today. Larison mentions Canadian philosopher George Grant, a critic of bigness in both economic and political institutions. “Over 40 years ago, Canadian philosopher George Grant said that American conservatives must oppose economic centralization if they seriously hope to pursue political decentralization.”

Considering the state of America’s economic system today, it’s hardly surprising that this issue focuses chiefly on economics.

Considering the state of America’s economic system today, it’s hardly surprising that this issue focuses chiefly on economics.

Stuart Klawans reviews

Stuart Klawans reviews

Gary Younge

Gary Younge

Chronicle

Chronicle