In this issue, Kim Phillips-Fein looks at a topic we spend a significant amount of time on here at Los Thunderlads, the political label “conservative” and the odd collections of people and ideas that have been grouped under it over the years. Phillips-Fein faces an impossible task; her 3-page piece is packaged as a review essay on 12 books, and as she goes she is constrained to mention several more books and articles. What she has written would be a fine introduction to a bibliography on recent scholarship about the American Right. There is one snippet in the piece I’d like to quote. Describing the attempt by New York Times writers David Brooks and Sam Tanenhaus to enshrine a traditionalist conservatism of the sort that writers like Irving Babbitt, Russell Kirk, and George Nash found in the writings of Edmund Burke, Phillips-Fein expresses skepticism that such a conservatism is likely to flourish in America. “That Brooks and Tanenhaus find the motif of Burke appealing is largely a sign of their longing to revive a serious, sophisticated and mature conservatism, and their sense that, thanks to the radicals, the right is in desperate straits and has entered a period of decline.”

In this issue, Kim Phillips-Fein looks at a topic we spend a significant amount of time on here at Los Thunderlads, the political label “conservative” and the odd collections of people and ideas that have been grouped under it over the years. Phillips-Fein faces an impossible task; her 3-page piece is packaged as a review essay on 12 books, and as she goes she is constrained to mention several more books and articles. What she has written would be a fine introduction to a bibliography on recent scholarship about the American Right. There is one snippet in the piece I’d like to quote. Describing the attempt by New York Times writers David Brooks and Sam Tanenhaus to enshrine a traditionalist conservatism of the sort that writers like Irving Babbitt, Russell Kirk, and George Nash found in the writings of Edmund Burke, Phillips-Fein expresses skepticism that such a conservatism is likely to flourish in America. “That Brooks and Tanenhaus find the motif of Burke appealing is largely a sign of their longing to revive a serious, sophisticated and mature conservatism, and their sense that, thanks to the radicals, the right is in desperate straits and has entered a period of decline.”

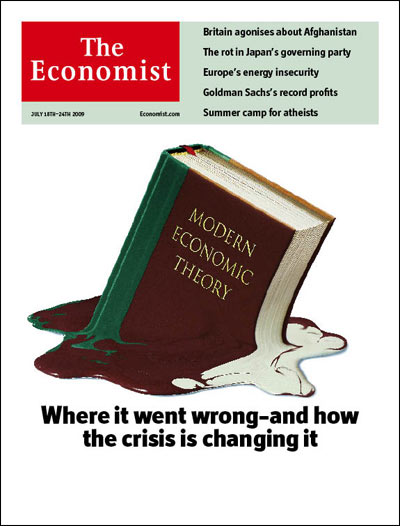

I don’t know whether Tanenhaus and Brooks believe that the American Right is in decline as a political force. I for my part find it hard to escape the conclusion that it is in a very bad way as an intellectual tradition. Readers of this blog will have noticed that I spend a lot of time reading magazines like The American Conservative and Chronicles; so it shouldn’t be surprising that I sympathize with their desire to provide America with a conservatism worth arguing against.

A column about Harvard Medical School’s vague conflict-of-interest policy mentions the fact that some researchers at that institutions have received over $1 million dollars from companies they are supposed to be observing disinterestedly. Its dean “wants to increase, not decrease, the school’s connections with industry.”